Introduction

LLMs perform well on coding benchmarks like LiveCodeBench but struggle with real-world software engineering (SWE) tasks (Jimenez et al. 2024). Even large models like Claude reach only around 60% accuracy on SWE-bench, despite using carefully engineered prompting pipelines (Xia et al. 2024). Smaller models (under 100B parameters) perform significantly worse, typically scoring below 10% in zero-shot settings and plateauing around 30% after supervised fine-tuning (SFT) (Pan et al. 2024, Xie et al. 2025) on GitHub issue datasets. Improving the performance of these small models remains a key challenge for practical deployment, where repeatedly querying large models is often too costly or inefficient.

Existing approaches primarily rely on supervised fine-tuning (SFT) with high-quality data, which is expensive to curate at scale. An alternative is test-time scaling: generating multiple outputs, scoring them using a verifier, and selecting the best one. Although effective, this strategy often requires excessive sampling and costly scoring. This work aims to explore a new research direction: sample-efficient test-time scaling methods that can identify correct solutions with fewer samples. We propose Evolutionary Test-Time Scaling (EvoScale) that treats generation as an evolutionary process. By iteratively refining outputs via selection and mutation, EvoScale shifts the output distribution toward higher-scoring regions. Our approach results in Satori-SWE-32B, a 32B model trained on open-source model and data. Key features of Satori-SWE include:

- A new perspective of formulating test-time scaling as an evolutionary process, improving sample efficiency for software engineering tasks.

- A novel RL training approach that enables self-evolution, eliminating the need for external reward models or verifiers at inference time.

- Satori-SWE-32B with EvoScale achieves performance comparable to models exceeding 100B parameters, while requiring only a small number of samples.

Our Approach

1. Preliminaries

We study the problem of using LMs to resolve real-world GitHub issues, where each issue consists of a textual description and a corresponding code repository. This work follows pipeline-based methods that decompose the task into retrieval and editing. Retrieval refers to identifying the files or functions relevant to the issue, while editing involves generating the code changes needed to resolve it.

Formally, given an issue description $x$, the goal is to produce a code edit (i.e., patch) $y$ that fixes the bug or implements the requested change. A retrieval model selects a subset code context $C(x) \subseteq \mathcal{C}$ from the full codebase $\mathcal{C}$, and an editing model $\pi$ generates the patch $y = \pi(x, C(x))$ that modifies the code context $C(x)$. While retrieval has reached around 70% accuracy in prior work, editing remains the main bottleneck. This work focuses on improving editing performance in the pipeline-based setting, using off-the-shelf localization methods in experiments.

Why is test-time scaling sample-inefficient in SWE task?

Test-time scaling improves model performance during inference without training. For SWE task, correct solutions exist but are rarely sampled. As for hard issues, the model’s output distribution is not concentrated around high-scoring regions. The figure below shows reward score distribution of outputs from a SFT model, with high-scoring outputs concentrated in the long tail. Given a sample budget $N$, typical test-time scaling methods in SWE (Pan et al. 2024, Wei et al. 2025) draw $N$ outputs (patches) { ${y_i}$ }$_{i=1}^{N}$ from a frozen editor model $\pi$, score them with a score function $R$ (e.g., reward model or unit tests), and selects the best one $\arg\max_{y_i} R(x, y_i)$. While high-scoring outputs near the mode could be sampled easily, the challenge of test-time scaling is to identify high-scoring outputs from the tail of $\pi(\cdot \mid x, C(x))$. However, doing so typically requires a large sample size $N$, making the process sample-inefficient.

2. Formulation: Patch Generation as Evolution

Can a language model naturally perform mutation?

Ideally, the mutation operator should generate patches that improve scores. However, we find that models trained with classical SFT—conditioned only on the issue and code context—struggle to refine existing patches. To this end, we propose a two-stage SFT to overcome this limitation.

3. Small-scale Mutation SFT

We introduce a two-stage supervised fine-tuning (SFT) process: classical SFT followed by mutation SFT. The classical SFT model is first trained and then used to generate conditioning examples for training the mutation SFT model.

- Classical SFT: We fine-tune a base model on inputs consisting of the issue description $x$ and code context $C(x)$, with targets that include a chain-of-thought (CoT) trace and the ground-truth patch, jointly denoted as $y^*_{\text{SFT}}$. The training objective is:

- Mutation SFT: We fine-tune a second model, initialized from the same base model, using inputs $x$, $C(x)$, and a set of conditioning examples $\mathcal{E}$ consisting of patches sampled from the classical SFT model $\pi_{\text{SFT}}$. The target $y^*_{\text{M-SFT}}$ includes a CoT trace generated by the teacher model $\mu$ conditioned on $\mathcal{E}$, along with the ground-truth patch. The training objective is:

Can SFT Model after the two-stage training learns to self-evolve?

Self-evolution requires the model to improve low-scoring patches on its own, without relying on reward models to select high-scoring examples. If so, we could eliminate the selection step (Line 3 in Algorithm), reducing scoring costs and sample usage. However, we find that SFT alone cannot enable self-evolution. We then introduce a reinforcement learning approach that trains the model to self-evolve without scoring or filtering.

4. Large‑Scale RL for Self‑Evolution

To self-evolve, the model must generate patches that maximize a scoring function $R$, given conditioning examples $\mathcal{E}$ from previous patches. This setup naturally aligns with reinforcement learning (RL), where a policy $\pi$ is optimized to maximize expected rewards (i.e., scores) over time. Since our goal is to maximize the reward at the final iteration $T$, a naïve RL objective is:

- Rewards are sparse, with feedback only at iteration $T$, making learning inefficient (Shen et al. 2025, Lee et al. 2024).

- Generating full $T$-step trajectories is computationally expensive (Snell et al. 2025).

We address the sparse reward challenge using potential-based reward shaping (Ng et al. 1999), where the potential function is defined as $\Phi(y) = R(x, y)$. The potential reward at step-$t$ is:

In practice, we fine-tune the mutation SFT model $\pi_{\text{M-SFT}}$ to maximize the expected potential rewards in score between a newly generated patch $y$ and a previous patch $y^\prime$ drawn from the conditioning examples $\mathcal{E}$:

Benchmarking Performance on SWE‑Bench‑Verified

We use the Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct model as our base model for training Satori-SWE-32B. Through the two-stage SFT training and RL training, Satori-SWE-32B outperforms all small-scale models under greedy decoding, while achieving comparable performance with current SOTA SWE-RL with smaller model scale (32B v.s. 70B), much fewer training data (30K v.s. million-scale) and test-time scaling samples (50 v.s. 500).

| Model | Params | Best@N | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT‑4o (Agentless) | – | 1 | 38.8 |

| Claude 3.5 (Agentless) | – | 1 | 50.8 |

| DeepSeek‑V3 (Agentless) | – | – | 42.0 |

| SWE‑Fixer | 72 B | 1 | 30.2 |

| SWE‑Gym‑32B | 32 B | 1 | 20.6 |

| SWE‑Gym‑32B | 32 B | 16 | 32.0 |

| Llama‑3 SWE‑RL | 70 B | 80 | 37.0 |

| Llama‑3 SWE‑RL | 70 B | 500 | 41.0 |

| Satori‑SWE‑32B | 32 B | 1 | 35.8 |

| Satori‑SWE‑32B | 32 B | 10 | 38.9 |

| Satori‑SWE‑32B | 32 B | 25 | 40.2 |

| Satori‑SWE‑32B | 32 B | 50 | 41.6 |

Anaysis of SWE-Satori

We further present a comprehensive analysis of the proposed EvoScale approach. To simplify our analysis, we use ground-truth localization (retrieval) and focus on the code editing part.

Can LLMs Iteratively Evolve without Mutation SFT Training?

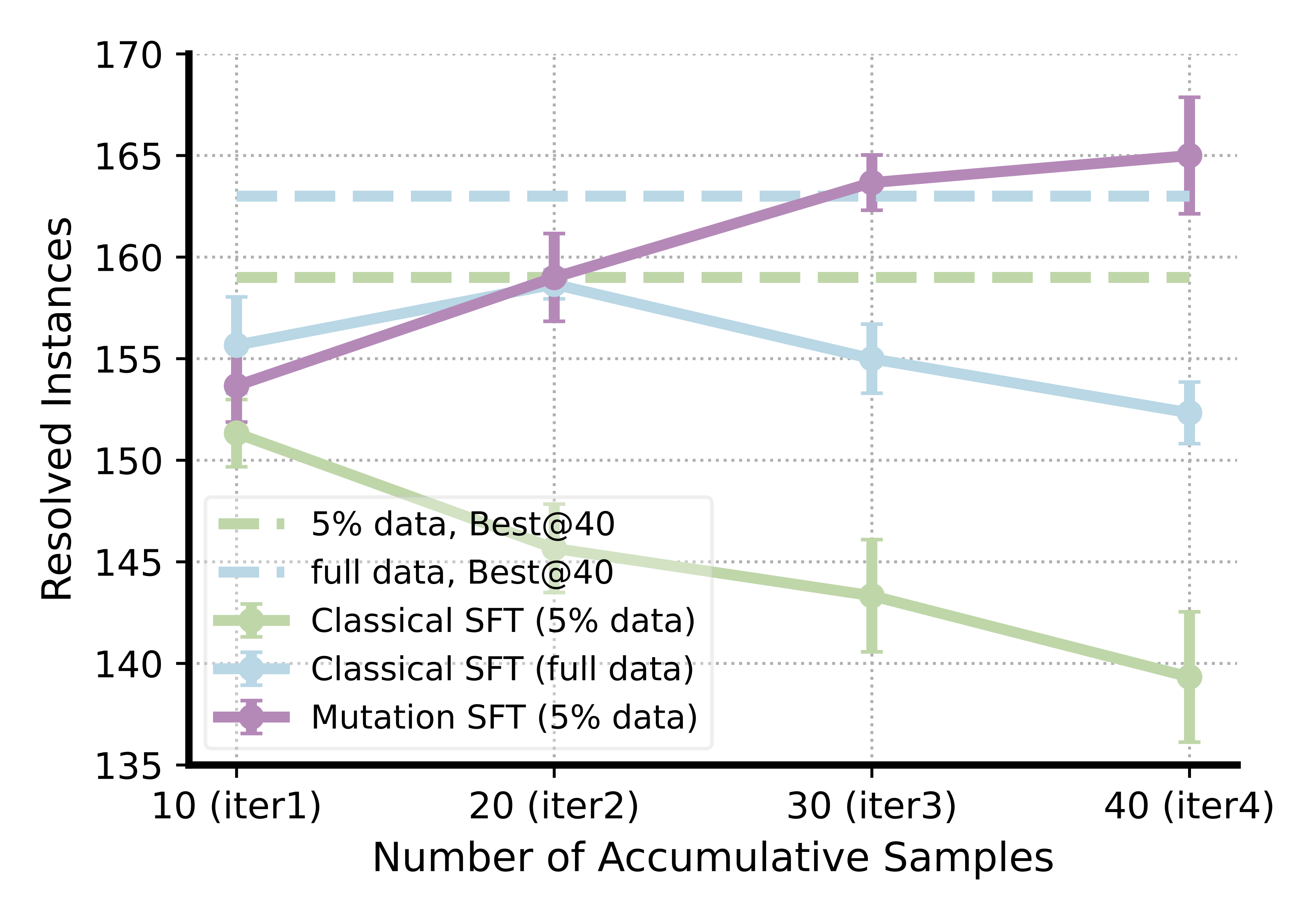

First, we investigate whether the mutation SFT is necessary for LLMs to learn how to iteratively improve their generations. Specifically, we fine-tune base LLMs using either classical SFT (without conditional generation) or mutation SFT. As shown in Figure, models trained with classical SFT fail to naturally improve their outputs when conditioned on previous samples. In contrast, mutation SFT enables the model to iteratively improve under the guidance of a reward model. The performance of the mutation SFT model at later iterations can surpass the classical SFT model by scaling up the samples (e.g., Best@40). Moreover, this iterative refinement capability can be learned effectively even with a small number of training data.

RL Enables Self-evolve Capability.

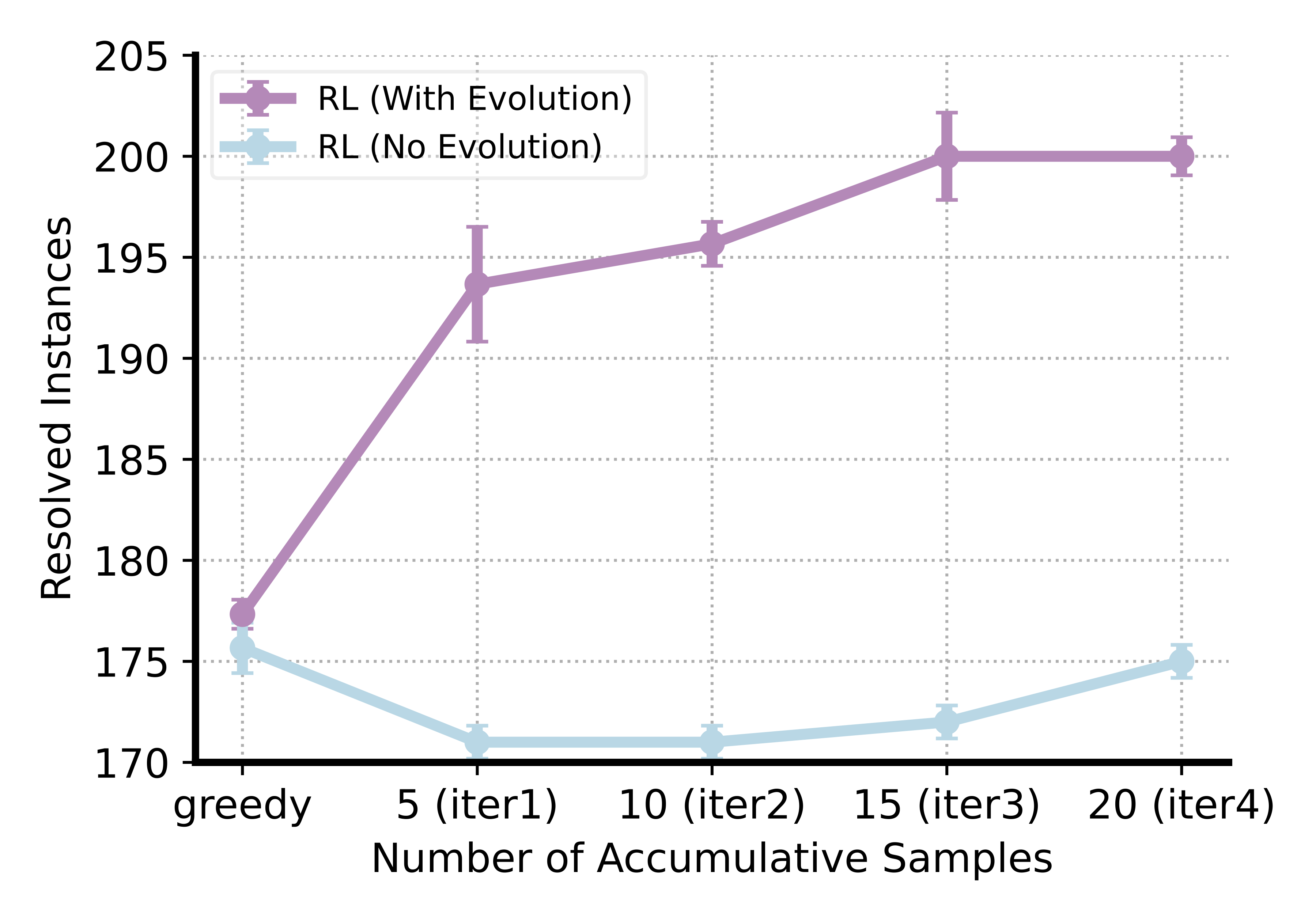

While mutation SFT model demonstrates evolutionary behavior when guided by a reward model, we further examine whether it can self-evolve without such guidance. Specifically, instead of selecting the top-$K$ candidates to ensure generation quality, we allow the model to generate $M=K=5$ random samples for the next iteration of conditional generation. However, the SFT model fails to learn self-evolution without reward model selection. Interestingly, RL training significantly improves the SFT model in two key aspects. First, RL substantially boosts the model’s greedy performance, surpassing even the Best@$N$ performance of 30 randomly generated samples from the SFT model. Second, we observe that the RL-trained model exhibits strong self-evolution capability: even when conditioned on its random outputs, the model can self-refine and improve performance across iterations without reward model guidance.

Do our SFT and RL Models Monotonically Improve Reward Scores over Iterations?

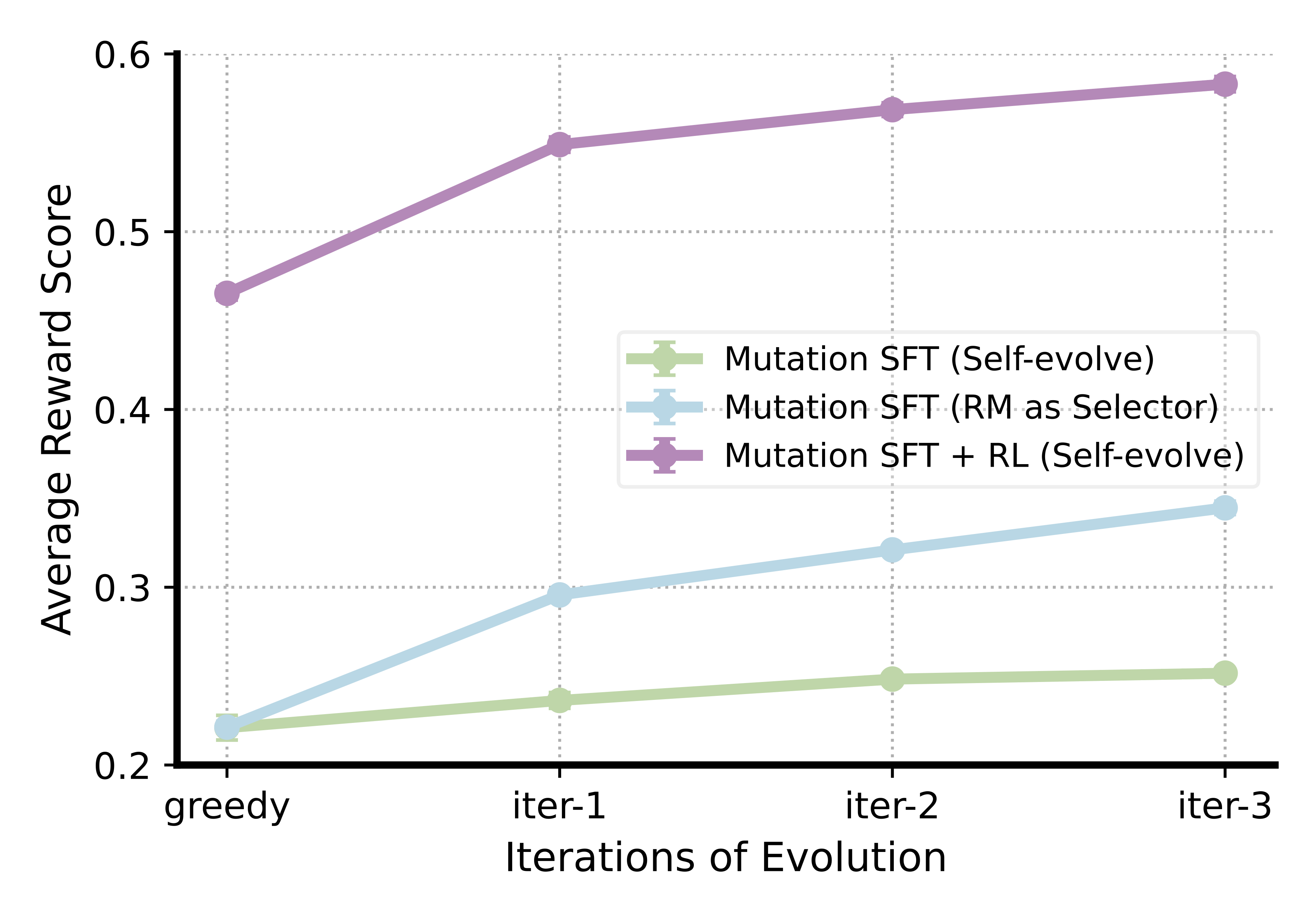

We further analyze the evolutionary behavior of the SFT and RL models by measuring the average reward score of the patch samples generated at each iteration. As shown in the Figure, although the SFT model learns to iteratively improve reward scores, it relies on the reward model to select high-quality conditioning examples to achieve significant improvements. In contrast, the RL model trained with potential-based reward, naturally learns to self-evolve without any external guidance. Its reward scores improve monotonically across iterations.

Evolutionary Test-time Scaling v.s. Other Test-time Scaling Methods.

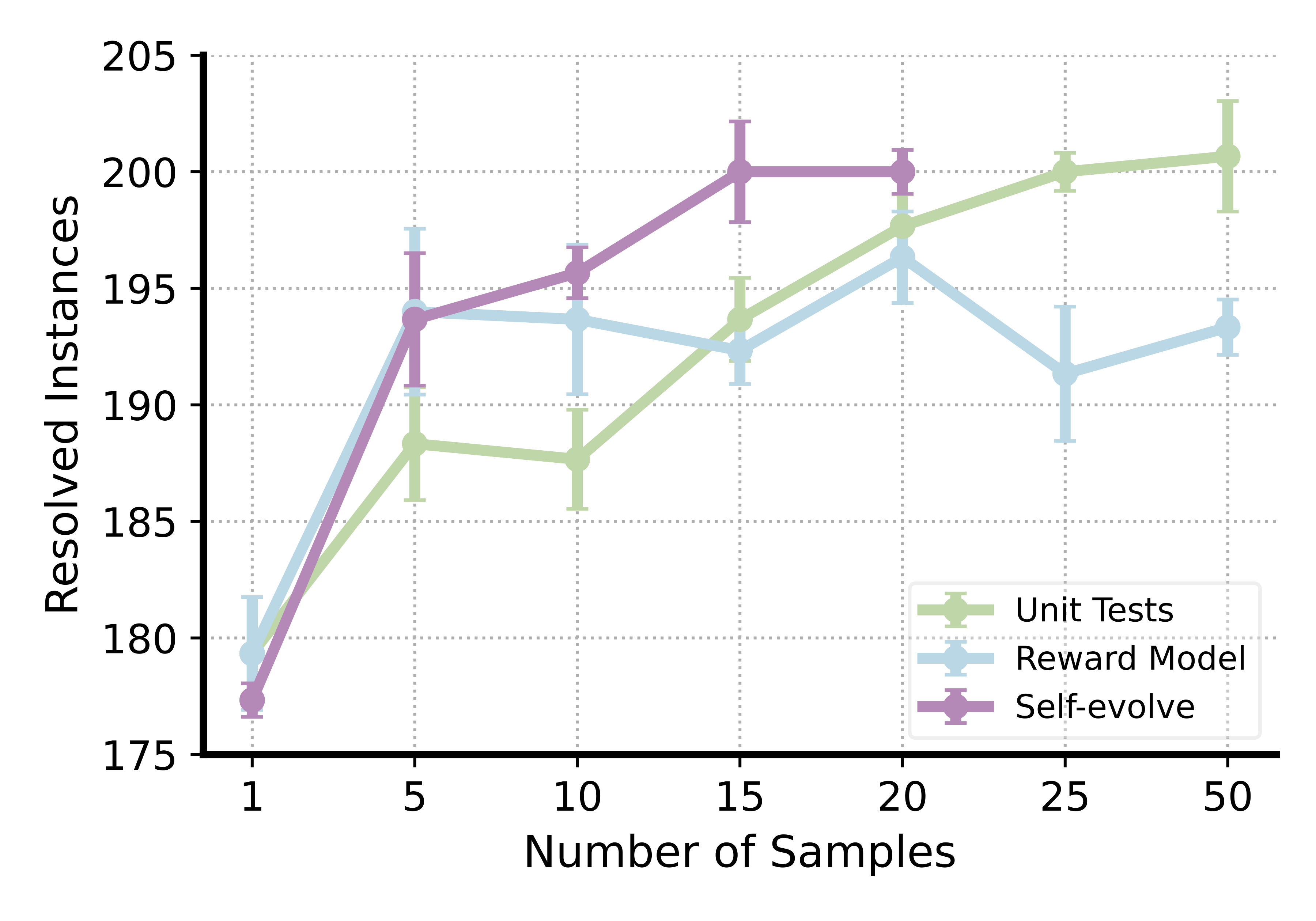

Next, we further compare evolutionary test-time scaling with other test-time scaling methods. Starting from the RL model, we first randomly sample $N={5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 50}$ patch samples and let the reward model and unit tests select the best sample among the subsets. Also starting from the RL model, we let the model perform self-evolution with $K=5$ samples per iteration, up to four iterations ($20$ samples in total). The test-time scaling results presented in the Figure demonstrate both efficiency and effectiveness of evolutionary test-time scaling.

Demo Examples

The core idea of EvoScale is to use a mix of correct and incorrect patches as context to generate a correct patch. In this part, we present an example below to illustrate the capability.

Issue Description

>>> Contains(x, Reals).as_set()

Contains(x, Reals)

This is wrong because Contains is not a set (it’s a boolean).

It causes failures elsewhere because Contains lacks as_relational

(since it isn’t a set). For example

(from https://github.com/sympy/sympy/pull/14965#discussion_r205281989):

>>> Piecewise((6, Contains(x, Reals)), (7, True))

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./sympy/functions/elementary/piecewise.py", line 136, in __new__

r = cls.eval(*newargs)

File "./sympy/functions/elementary/piecewise.py", line 185, in eval

c = c.as_set().as_relational(x)

AttributeError: 'Contains' object has no attribute 'as_relational'

Conditional Patches

Conditional patch 1 ✅

diff --git a/sympy/sets/contains.py b/sympy/sets/contains.py

index 0b1e933..3fd780b 100644

--- a/sympy/sets/contains.py

+++ b/sympy/sets/contains.py

@@ -45,4 +45,6 @@ class Contains(BooleanFunction):

def as_set(self):

- raise NotImplementedError()

+ # The set being contained in is the only set we can return

+ # from a Contains object in any meaningful way

+ return self.args[1]

Conditional patch 2 ✅

diff --git a/sympy/sets/contains.py b/sympy/sets/contains.py

index 0b1e933..4c089aa 100644

--- a/sympy/sets/contains.py

+++ b/sympy/sets/contains.py

@@ -45,4 +45,5 @@ class Contains(BooleanFunction):

def as_set(self):

- raise NotImplementedError()

+ # The set that is being tested for contains

+ return self.args[1]

Conditional patch 3 ✅

diff --git a/sympy/sets/contains.py b/sympy/sets/contains.py

index 0b1e933..985c88e 100644

--- a/sympy/sets/contains.py

+++ b/sympy/sets/contains.py

@@ -45,4 +45,6 @@ class Contains(BooleanFunction):

def as_set(self):

- raise NotImplementedError()

+ # The set being contained in is the set representation

+ # of Contains objects

+ return self.args[1]

Conditional patch 4 ✅

diff --git a/sympy/sets/contains.py b/sympy/sets/contains.py

index 0b1e933..e732791 100644

--- a/sympy/sets/contains.py

+++ b/sympy/sets/contains.py

@@ -45,4 +45,6 @@ class Contains(BooleanFunction):

def as_set(self):

- raise NotImplementedError()

+ # Contains(x, S) means "x is in S", so as_set returns S

+ return self.args[1]

Conditional patch 5 ❌

diff --git a/sympy/sets/contains.py b/sympy/sets/contains.py

index 0b1e933..4980364 100644

--- a/sympy/sets/contains.py

+++ b/sympy/sets/contains.py

@@ -45,4 +45,22 @@ class Contains(BooleanFunction):

def as_set(self):

+ # try to evaluate Contains(x, S)

+ try:

+ res = self._eval_evalf()

+ if res == S.true:

+ return S.UniversalSet

+ elif res == S.false:

+ return S.EmptySet

+ except (TypeError, AttributeError):

+ pass

+ # fallback

raise NotImplementedError()

Evolve Response

Thinking Process

Patch 1: This patch correctly identifies that the set being contained in (self.args[1]) is the most meaningful set representation of a Contains object. The implementation is simple and correct.

Patch 2: Similar to Patch 1 but with slightly different wording in the comment. The functionality is correct but the comment could be more precise about why this is the right approach.

Patch 3: This patch adds a note about potential invalid sets, which isn’t strictly necessary since the issue is about the basic behavior. The core implementation is correct but the comment is overly cautious.

Patch 4: This patch provides a clear explanation of why returning the set (self.args[1]) is the correct behavior - because Contains(x, S) means “x is in S”, so the set representation is just S. This is a correct and well-explained solution.

Patch 5: This patch takes a different approach by trying to evaluate the Contains expression and return either the universal or empty set based on the result. While creative, this doesn’t match the simple and correct solution of just returning the set being contained in. The approach is overly complex for this simple issue.

Issue Analysis:

- The issue occurs when Contains.as_set() returns the Contains object itself instead of a proper set.

- This causes problems because other code expects a set with as_relational() method.

- The correct behavior should be to return the set that x is being tested for containment in (self.args[1]), since that’s the only meaningful set representation of a Contains object.

Solution Approach:

- The simplest and most correct solution is to modify as_set() to return self.args[1], which is the set being tested for containment.

- This matches the mathematical interpretation that Contains(x, S) means “x is in S”, so the set representation is just S.

- No other evaluation or special cases are needed since the set being contained in is the only meaningful set representation of a Contains object.

Code Localization:

- The issue is in sympy/sets/contains.py in the Contains class.

- The problematic method is as_set() which currently raises NotImplementedError.

- The fix is to modify this method to return self.args[1].

Evolved Patch ✅

diff --git a/sympy/sets/contains.py b/sympy/sets/contains.py

index 0b1e933..e732791 100644

--- a/sympy/sets/contains.py

+++ b/sympy/sets/contains.py

@@ -45,4 +45,6 @@ class Contains(BooleanFunction):

def as_set(self):

- raise NotImplementedError()

+ # Contains(x, S) means "x is in S", so as_set returns S

+ return self.args[1]

Commitment to Open-Source Community

We plan to provide the following resources:

- 📜 Paper with detailed implementation details in Appendix.

- 🧩 SFT data with CoT, Mutation SFT data with CoT, and RL data.

- ⚙️ Code for EvoScale Inference Piepline & RL training framework.

- 🏋️♂️ Model Checkpoints:

- Code Editing Model (SFT):

Satori‑SWE‑SFT-32B - Code Editing Model (RL):

Satori‑SWE‑RL-32B - Code Editing Reward Model:

Satori‑SWE‑RM-32B - Retrieval Model:

Satori‑SWE‑Retrieval-32B - Retrieval Reward Model:

Satori‑SWE‑Retrieval-RM-32B

- Code Editing Model (SFT):

Stay tuned on our GitHub.

Satori Team Members

$†$: Project lead

Core Contributors

Contributors

- Delin Chen, UMass Amherst

- Zhenting Qi, Harvard

- Wei Lu, SUTD

- Gregory W. Wornell, MIT

- Subhro Das, MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab

- David Cox, MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab

- Chuang Gan$^†$, UMass, MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab

Contact Information

For questions, please:

- Raise an issue in our GitHub repository

- Contact us at: satori2025@outlook.com

Citation

@misc{zeng2025satorisweevolutionarytesttimescaling,

title={Satori-SWE: Evolutionary Test-Time Scaling for Sample-Efficient Software Engineering},

author={Guangtao Zeng and Maohao Shen and Delin Chen and Zhenting Qi and Subhro Das and Dan Gutfreund and David Cox and Gregory Wornell and Wei Lu and Zhang-Wei Hong and Chuang Gan},

year={2025},

eprint={2505.23604},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CL},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.23604},

}